For most, Port Douglas is the end of the road to the North, a comfortable, if dull, collection of resorts, restaurants, bars and boutiques. For RLS, though, it is the starting point for journeys into a region that is at once remote and the centre of trade routes, teeming with marine life and threatened with danger, a meeting place of ancient cultures of Australia and the Pacific and the scene of historical and political drama. The chance to join Eviota is a wonderful opportunity at any time, but the enticements and mysteries of the Coral Sea held out the promise of an exceptional experience for Amelia Fowles and Bill Barker, who Joined Graham Edgar on this trip.

Leaving Port Douglas on the afternoon of 29 November, we made the short crossing to the Low Isles. This was a fitting start to our surveys, as it was the site of an expedition of British scientists in the late 1920s, the first intensive modern scientific investigation of the Great Barrier Reef. Unfortunately, time and human influence have not been kind to this place, but at least it made for a comparatively easy start to our dive program.

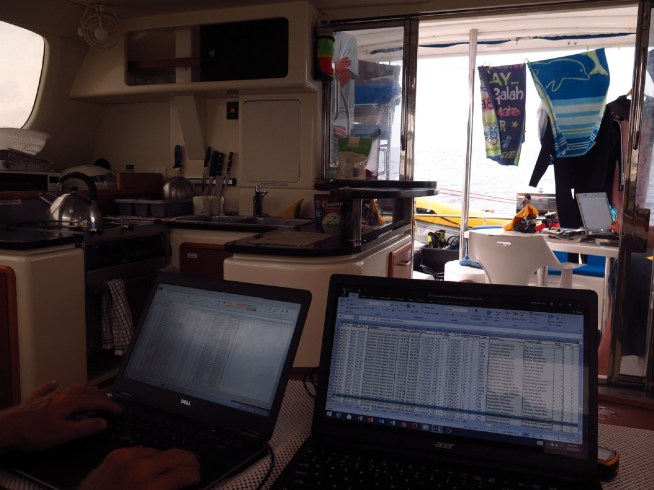

An overnight passage then took us to Bougainville Reef, named after the French navigator, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville who, in one of history’s great “what ifs?”, was turned away by the breakers of the reef during his search for the Great South Land in 1768. Rising abruptly from the ocean bed almost two kilometres below, the reef is a dramatic place to dive. We emerged from the water exhilarated by our experience, the sheer fall of the face of the wall and the multitude of fish that swirled around us. The only downside, as always, is that the more marine life, the more challenging the task of data entry.

Another night passage took us north to Osprey Reef. This is regularly visited by liveaboard dive boats, but such organised experiences cannot compare with that of the independent expedition. Osprey is a huge atoll, 25 kms by 12 kms, enclosing a deep lagoon that is more like a large lake. We stayed there for several days, diving both inside and outside the lagoon, on bommies, in shallows and on the precipitous walls. One dive was at North Horn, where the tourist operators take divers for a shark feeding experience. On dropping into the water we were immediately greeted by a dozen or so sharks, mostly grey reef, with a few white tips. No doubt disappointed when no food was on offer, most of them dropped off after ten minutes or so, but we were accompanied by two or three white tips, which persistently swam around us as we were doing our surveys. The corals at North Horn look degraded but the site was nevertheless very rich in marine life. The good weather meant that we were able to carry out surveys virtually every day.

From Osprey we returned to the Barrier Reef. Our first stop was Tydeman Cay, where we did a couple of surveys, but the highlight was a brief trip to the cay itself. These cays may have a lonely and forlorn aspect, but they support a lively assemblage of breeding seabirds, which give a welcome of sorts to the infrequent visitor. We found hundreds of boobies nesting there, with their offspring at all stages from eggs to large fluffy chicks. A memorable experience was when we came across a turtle returning to the sea after having laid her eggs overnight. She dragged her heavy weight laboriously over the sand, resting occasionally. As she entered the sea, we shared her satisfaction at the return of her buoyancy as she took off and then swam vigorously into her natural element. For us there was a moment of reflection on this age-old cycle of renewal, in a place remote from human influence.

Heading north again, but still within the Barrier, we did a survey at a place called Lagoon Reef, which had a profusion of healthy coral and myriad fish life and typified the conventional idea of what the Barrier Reef should look like. From there it was the start of a longer overnight journey to Ashmore Reef. As soon as we were outside the passage through the Barrier we encountered a sizeable swell to go with the 20 knot winds. This kept up all night. Eviota held stoutly to her task, but, for those on board, food and sleep were not easy and it was a bleary eyed and hungry crew who welcomed the shelter of Ashmore the next day. Ashmore was similar to Osprey, a giant rampart rising straight from the sea bed, with a large lagoon. There is a diverse range of survey sites within and outside the lagoon where we again encountered a rich marine life. The survey count continued to increase.

From Ashmore we went even further north to Boot Reef, almost on the Papua New Guinea border. This is the remotest of the remote, virtually unknown to anyone but a few specialists. Our approach was in keeping with the best traditions of the early navigators. As there is no passage into the lagoon, team leader Graham got into the water to make sure there was enough water for Eviota to clear the corals clawing the surface. With additional lookouts posted on both bows, we glided across the top of the reef at high tide to seek a sheltered and safe place to anchor.

Boot Reef was a wild and spectacular culmination to our journey. The lagoon presented an outstanding profusion of fish and corals. The mighty walls were the preserve of exciting pelagics. For Amelia and Bill, the highlight of sorts was a dive on Boot Rock, which was something of a Boot Reef on steroids. We are all used to carrying out surveys while sharks are patrolling – you get on with the job, while keeping a wary eye on the masters of the reef. On this occasion, however, things were a bit too hectic. The visibility wasn’t outstanding, about 20 metres, and the sharks just wouldn’t go away. The five or so Grey Reef Sharks who kept checking on us were quickly joined by two Silvertips. We stuck to our task and stuck together, though we realised that the distractions would inevitably reduce our species numbers. We were approaching the end of our first transect when things suddenly became a lot more complicated. A huge school of surgeonfish rocketed up the wall, closely pursued by 15 or so Grey Reef Sharks swimming up, down and around us at great speed. I’ve witnessed controlled shark feeds, but being in the water with sharks in large numbers doing what they do naturally is a completely different experience. Not knowing how many other sharks were just outside our field of vision or what might happen next, we didn’t take long to agree that this dive was over. In true RLS style we retrieved our tape and made our way carefully and warily to the surface. We missed a transect but left with a good story to tell.

From Boot we made our way west to the Torres Strait, a maze of islands, reefs and currents that has always posed a challenge for navigators. Our first survey was at Waier Island, within sight of Mer, the subject of the Native Title claim that changed Australian history. Two more surveys and our work was nearly done. On our last day as we were making for Thursday Island we were hoping to do a final dive that would stand out in the experience of anyone who has donned a mask: descending to the Quetta, which hit a rock here in 1890 with the loss of 134 lives. But despite the encouragement given by the tidal forecast, the scene on the spot was of a turbulent current that posed too many dangers. Prudence prevailed and of course there’s always another day for a dive. So it was on to Thursday Island, which provided an engaging South Pacific welcome. A part of Australia but fundamentally different, this haven was a perfect place to unwind and restore ourselves and the Eviota to a more civilised state.

The results of our expedition? Lots of surveys, of course, to add to the impressive total that RLS has built up in this remote area; completed, thanks to generally good weather, in good time and according to schedule. And for the individuals? “Fulfilled an aspiration of many years’ standing” (Bill Barker); “I was amazed by the beauty of our Commonwealth Marine Reserves …” (Amelia Fowles). And the final word from our team leader, Graham Edgar: “thanks to an ace team for a great trip to the most diverse reefs in Australia, but so much bleached and dead coral …..”.